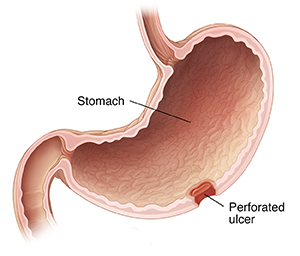

A peptic ulcer is an open sore in the stomach lining or the upper part of the small intestine (duodenum). An ulcer can go through all the layers of the digestive tract and form a hole (perforation). This is called a perforated ulcer. A perforated ulcer lets food and digestive juices leak out of the digestive tract. This is a serious health problem that needs urgent medical attention.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) occurs when there is an imbalance between stomach acid-pepsin and the protective barriers of the stomach lining. It affects about 4 million people worldwide every year. The incidence of PUD is estimated to be around 1. % to 3%. While complications can arise in 10% to 20% of PUD patients, only 2% to 14% of ulcers will actually perforate, leading to a sudden illness [Bertleff MJ, Lange JF, 2010]. Perforation is a serious complication of PUD, and patients with a perforated peptic ulcer (PPU) often present with severe abdominal pain that carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality [Bas G, Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Sahin M. 2008].

Previous studies have shown that seasonal changes may affect the occurrence of PPU, but other studies have not been able to confirm this pattern. In developing countries, PPU is more commonly found in young male smokers, while in developed countries, it tends to affect older individuals with multiple underlying health conditions and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or steroids. Risk factors for PPU include the use of NSAIDs, the presence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, physiological stress, smoking, corticosteroid use, and a history of previous PUD. Even with successful initial treatment, ulcer recurrence is common in individuals with these risk factors.

Symptoms of a perforated ulcer

Symptoms of a perforated ulcer may include:

⦁ Sudden, severe pain in the belly (abdomen), usually in the upper abdomen

⦁ Pain spreading to the back or shoulder

⦁ Upset stomach (nausea) or vomiting

⦁ Lack of appetite or feeling full

⦁ Swollen belly or feeling bloated

What causes perforated ulcers?

A hole will form if peptic ulcers go untreated. To find the cause of your ulcer, your healthcare provider will give you an exam and review your health history. They may also order tests. The main causes of peptic ulcers include:

⦁ Infection with the H. pylori (Helicobacter pylori) bacteria. This damages the stomach lining. Digestive juices can then harm the digestive tract.

⦁ Long-term use of some over-the-counter pain medicines such as NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). These include ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin. This makes stomach or intestinal damage more likely.

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are widely used for its analgesic, anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic effects. NSAID use is known to increase the risk of PPU. About a quarter of chronic NSAID users will develop PUD and 2%-4% will bleed or perforate. Drug interaction with steroids and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors also increases the risks of PUD. Selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors are less associated with PUD. A study in western Denmark showed that the standardized hospitalization rates for PPU reduced from 17 per 100000 population in 1996 to 12 per 100000 population in 2004 (HR 0.71; 95%CI: 0.57-0.88) after the introduction of selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors into clinical practice.

H. pylori

H. pylori remain one of the commonest infections worldwide. The prevalence of H. pylori has decreased in developed countries due to improved hygiene and reduced transmission in early childhood. The mean prevalence of H. pylori in patients with PPU varies between studies due to different diagnostic methods and geographical variations. Recurrent PUD mainly occurs in patients with H. pylori infection suggesting that H. pylori play an important role in the development of PUD and its complications. The risk of recurrent H. pylori infection is significantly reduced with proton pump inhibitor therapy, but proton pump inhibitors have only a modest efficacy for reduction in ulcers with NSAID users.

Smoking

Tobacco is thought to inhibit pancreatic bicarbonate secretion, leading to increased acidity in duodenum. It also inhibits the healing of duodenal ulcers. A meta-analysis has indicated that 23% of PUD could be associated with smoking. However, in some studies, there was no difference in tobacco use between patients with non-H. pylori, non-NSAID duodenal ulcers and those with H. pylori related ulcers, indicating a limited role of smoking. This is in agreement with previous studies, which indicated that smoking did not increase the risk of ulcer recurrence once the H. pylori had been eradicated.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical manifestation can be divided into three phases.

⦁ In the initial phase within 2 h of onset, epigastric pain, tachycardia and cool extremities are characteristic.

⦁ In the second phase (within 2 to 12 h), pain becomes generalized and is worse on movement. Typical signs such as abdominal rigidity and right lower quadrant tenderness (as a result of fluid tracking along the right paracolic gutter) may be seen.

⦁ In the third phase (more than 12 h), abdominal distension, pyrexia and hypotension with acute circulatory collapse may be evident.

DIAGNOSIS

⦁ An urgent erect chest X-ray and serum amylase/lipase is basic essential test in a patient with acute upper abdominal pain.

⦁ CT scan is recommended as it has a diagnostic accuracy as high. Besides, CT scan can exclude acute pancreatitis that would not need surgical intervention. CT scan is performed in supine position and free air is usually seen anteriorly just below the anterior abdominal wall.

⦁ Laboratory tests are performed in PPU not to establish diagnosis but to rule out differential diagnosis and also to understand the insult to various organ systems.

MANAGEMENT

Perforated Peptic Ulcer (PPU) is a surgical emergency associated with high mortality if left untreated. In general, all patients with PPU require prompt resuscitation, intravenous antibiotics, analgesia, proton pump inhibitory medications, nasogastric tube, urinary catheter and surgical source control.

Treatment for a perforated ulcer

Treatment for a perforated ulcer starts with fixing the hole in your digestive tract. This may be done with surgery.

Other treatments are aimed at easing pain and removing the cause of the ulcer. Prescription medicines may help with the following:

⦁ Reducing the amount of acid, the stomach makes

⦁ Coating the lining of the stomach and the duodenum

⦁ Treating infections

Drug treatment in PPU

Omeprazole and triple therapy for H. pylori eradication are useful adjuncts in treatment of PPU. Evidence has shown that omeprazole and triple therapy treatment reduces the recurrence rate significantly. Ulcer healing shown at 8-wk follow up with endoscopy was significantly higher in triple therapy eradication

Possible complications of a perforated ulcer

Perforated ulcers can have serious complications. These include:

⦁ Infection of the lining of the abdomen

⦁ Bloodstream infection

⦁ Death

LAPAROSCOPIC REPAIR

Laparoscopic repair was first performed for a perforated duodenal ulcer in 1990. Laparoscopic repair of PPU is believed to reduce the post-operative morbidity and mortality

Figure 2: Shows laparoscopic omental patch repair. A: Anterior duodenal perforation; B: Laparoscopic suturing; C: Omental patch; D: Abdominal drain placement.

CONCLUSION

PUD can now be treated with medications instead of elective surgery. However, PUD may perforate and PPU carries a high mortality risk. The classic triad of sudden onset of abdominal pain, tachycardia and abdominal rigidity is the hallmark of PPU. Erect chest radiograph may not establish the diagnosis and an index of suspicion is essential. Early diagnosis, prompt resuscitation and urgent surgical intervention are essential to improve outcomes. Non-operative management should be conducted by experienced teams with optimal resources and ideally under trial conditions. Exploratory laparotomy and omental patch repair remain the gold standard and laparoscopic surgery should be considered when expertise is available. Gastrectomy is recommended in patients with large or malignant ulcer to enhance outcomes; however, the outcomes of patients treated with gastric resections remain inferior. Gelatin sponge plugs, fibrin glue sealants, self-expandable stents and endoscopic clipping techniques deserve to be tested in a controlled trial setting.